By Terry E. McSween, founder and CEO, Quality Safety Edge

Last year I had the opportunity to speak with a group of 35 construction and maintenance contractors that were involved in active behavior-based safety (BBS) peer observation processes. I was invited to speak on the topic of improving peer safety observations.

The participants were mostly safety managers from their respective companies with a small number of other managers who worked in the field and had shared responsibility for safety. Also, this was not a random group drawn from the universe of organizations using BBS. They elected to come to a session that was billed as discussing common problems with BBS, so I assumed it was a group representing companies whose BBS programs were struggling with at least some aspects of the BBS process. I was not connected to the participating organizations in any way. I had not met them before nor had QSE worked with any of them. As a result, I had very little background concerning their organizations with which to frame our discussion. Luckily, we have begun using an audience response system that allows us tocollect data and receive feedback from our audience, so I decided to solicit some information from the audience on their specific problems with BBS observations.

The participants were mostly safety managers from their respective companies with a small number of other managers who worked in the field and had shared responsibility for safety. Also, this was not a random group drawn from the universe of organizations using BBS. They elected to come to a session that was billed as discussing common problems with BBS, so I assumed it was a group representing companies whose BBS programs were struggling with at least some aspects of the BBS process. I was not connected to the participating organizations in any way. I had not met them before nor had QSE worked with any of them. As a result, I had very little background concerning their organizations with which to frame our discussion. Luckily, we have begun using an audience response system that allows us tocollect data and receive feedback from our audience, so I decided to solicit some information from the audience on their specific problems with BBS observations.

Those of you who know QSE probably know that we are somewhat obsessed with data, so of course, I found the result of this assessment interesting. While the sample is not statistically random, this group provided insight into what I suspect many organizations struggle with in their BBS processes. In this issue, I thought I would share the results of this survey, and then use those data as the basis for the next several articles.

The Data

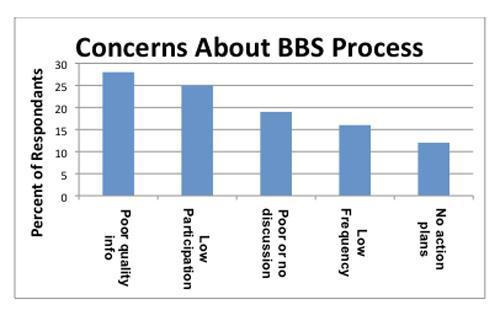

The 32 participants who responded to this item were most concerned about the issues shown on the following chart:

While I do not assume that we can generalize from this data to the broader population with a great deal of accuracy, this is currently the best data I have to suggest the problems that some of you may be struggling with in your BBS initiatives. So, with this data in hand, I plan to do a series of articles addressing each of these concerns, building on the details discussed with the participants of that session and several similar sessions conducted with some of QSE’s clients over the past year.

Poor Quality Information on Observation Checklists

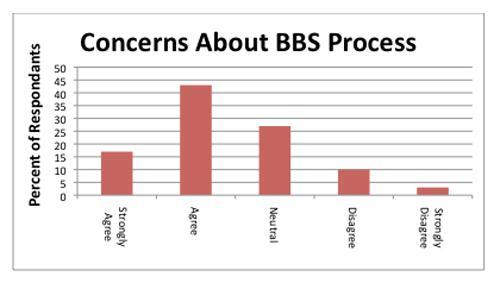

I was frankly surprised that this issue was selected by the most participants as their primary issue. Let me provide additional data on the extent of this issue within our sample population. A full 60 percent (18 of the 30 respondents to this item) either agreed or strongly agreed that getting quality information on the observation checklists was a big problem in their BBS process.

The discussion that followed brought clarity to the scope of the issue that the audience was responding to. Generally they had two concerns: (1) pencil-whipping or completed observations reporting 100% safe behaviors and (2) poor use of comments to clarify the situation and risks. I’d like to discuss both of those in the remainder of this article.

First, I’d like to make a few comments on “pencil-whipping” observation forms. I’ve heard the horror stories, such as original observation forms left on the copy machine, people filling out large stacks, and so on. In my experience, this is rarely a problem. Most people will do the job right and not lie or fabricate information to complete an observation—and if they do so, typically it is because they have a poorly designed process with the threat of significant penalties or significant rewards associated with submitting completed observations. In a well-designed process, I have rarely encountered this problem. Not one person in the group of 35 people in my audience reported this kind of abuse as a problem.

Now, I have seen an occasional person who uses an observation form to document something they saw earlier when they were not formally doing an observation. While this is not a typical observation, if the issue is important enough, I consider this a valid way to ensure the item is reviewed by the safety committee, or if the company has more appropriate avenues, the safety committee or leadership should simply coach the employee on the more appropriate process for raising safety issues.

The more common issue is observations that report 100% safe behavior. Almost always, an organization with broad employee involvement in safety observations will have a group of observers that regularly report that every behavior they observed was safe, and sometimes the only safety issues that they report on are related to safety conditions rather than behaviors. Several members of my audience reported problems of this nature.

Addressing 100% Safe Observations

Generally the Safety Committee (or BBS Steering Committee) has responsibility for addressing this issue. Most of the commercial databases for tracking observations simplify the process of finding observers who routinely turn in completed 100% safety observation checklists. Once those individuals are identified, the next step is for the Committee Members to conduct “calibration observations” with those observers. Calibration Observations involve going along with the employee and then comparing notes on what was observed and coaching the observer on recognizing and recording hazardous behaviors. As they are doing calibration observations, Steering Committee members need to analyze the factors that have contributed to the 100% safe reporting. In some cases, employees have trouble recognizing the hazard, which means the organization has a skill issue that needs to be addressed. If your observers are not recognizing one of the critical behaviors, probably other employees have that same problem. Addressing this hazard recognition deficit can often be done in a simple and effective way by taking pictures or videos that show both examples and non-examples of the target behavior.

In some cases, the 100% safe observations are not caused by a failure to recognize the hazard, but rather by a failure to accurately record what they see, more of a motivation issue. Again, the Steering Committee members need to listen closely to what the observers say about why they recorded only safe behaviors. Perhaps the most common cause for an employee to hesitate to record an unsafe practice is the fear of getting their coworker in trouble. In our group, several participants thought this was a factor that impacted on the accuracy of recording in their organizations. The way that we typically address this issue with our clients is to create a policy statement or leadership commitment statement that assures employees that the data from observations will not be used against employees. None of the participants reporting this problem had such a statement. Further, when I put the question to my audience, 100% (of the 32 people who responded) thought that such a statement, signed by management and communicated through all levels of the organization, would help address this problem.

One other important factor that impacts on observer’s motivation to accurately record both safe and unsafe practices comes from the Safety Committee’s use of the data to develop action plans. Not only do they have to develop and execute such action plans, they also have to communicate progress on those plans throughout the organization. Observers need to know that the data are important for supporting the organization’s safety improvement efforts.

The Lack of Useful Comments

When considering the lack of useful comments, the Safety Committee once again needs to analyze whether the root cause of this issue in their organization is related to skill or motivation. Often, being able to objectively describe the task and circumstances of an unsafe act is a pinpointing skill that needs to be taught and practiced in both observer and refresher training. More often however, a failure to record detailed comments is a motivation issue. First, the natural consequences work against getting good comments—writing good comments simply takes more effort than leaving the page blank. The only way to offset this natural consequence is by counteracting it with other positive consequences. The most important natural consequence for writing a good description is for the employee to see the Safety Committee use detailed information to help create effective action plans that get the causes of the unsafe act addressed. Often that is not enough however, as addressing the causes of unsafe practices often takes time. For this reason, the Safety Committee should try to provide positive feedback for good comments, and even provide regular recognition to observers who provide exemplary comments that clearly describe the task, the at-risk behavior, and the factors contributing to it. Such efforts by the Steering Committee provide the reasons employees need to take the time to provide good comments and thus are an important part of an effective BBS process.

In this case, “the lack of useful comments” is interrelated with one of the other problems experienced by our session participants, though it was the least frequent concern. If your process does not result in meaningful action plans, employees will not remain motivated to provide good comments. Each of the elements of BBS are inter-related; sometimes a weakness in one area contributes to a more obvious weakness in other areas. In the worst cases, you have observations that lack meaning and make no contribution to safety.

I look forward to discussing some of the other challenges experienced by my meeting participants in the next installment!