by Terry McSween, Ph.D.

In a previous article I shared the data collected from a group of 35 construction and maintenance contractors that had active behavior-based safety peer observation processes. In a session on common problems with behavioral observations, I used an audience response system to quantify the issues that participants were having with behavioral safety observations.

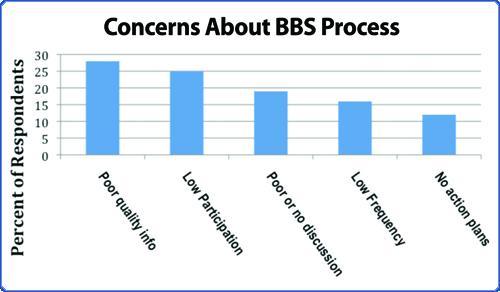

As a review of the “big picture” data that I included in the last issue, the 32 participants (out of a total of 35 audience members) who responded were most concerned about the issues shown on the following chart:

In this issue, I would like to summarize the discussion our group had on low participation in conducting observations, which was the second most frequently identified problem in our group. In fact, 28 percent of the participants identified poor quality information as their biggest problem, while 25 percent report low participation, so these two issues are roughly equivalent issues for companies with BBS initiatives.

Low Participation in BBS Observations

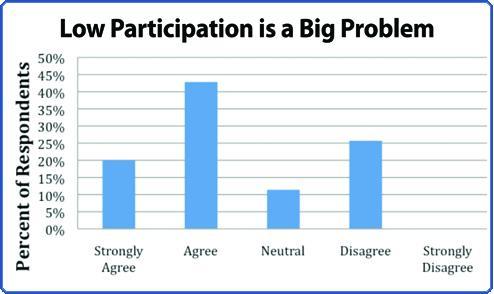

Here is the data on the extent of this issue within our sample population. A full 63 percent (22 of the 35 respondents to this item) either agreed or strongly agreed that getting employees to conduct BBS observations was a big problem in their BBS process, suggesting this is actually a more prevalent problem than getting employees to record quality information on BBS observation checklists. The data on this item is presented in the following chart:

In previous articles I have talked about the differences between having designated observers and asking all employees to participate. Many of you probably know that our bias is to involve all employees in conducting safety observations, in part because we have data to suggest that those who conduct BBS observations and coaching are less likely to be injured or involved in a safety incident. Regardless of the choice of designated or all-employee observations, this item suggests that companies struggle with getting their observers to conduct observations on a regular basis.

The following issues surfaced in the ensuing discussion of barriers to observations:

- Observers do not know how to discuss observations (or lack confidence).

- Observers do not see companies using the information.

- Production competes for available time (production pressure).

- Leadership does not communicate the importance of safety observations (formal or informal leaders).

I wish I had taken data on the extent of each of these issues to better quantify these barriers and how much they each contribute to the problem. Ah well, next time. Until then, let’s take a look at each of these issues.

Training Observers

Employees sometime do not conduct observations simply because they do not know how or lack confidence in their ability to discuss their observations. Good observer training should address this need by providing employees with the skills needed to clearly discuss their observations, how to objectively describe behavior, and how to discuss the potential of the behavior for having an impact on safety. Not only do observers need to know how to do these things, but they should get enough guided practice, either in a workshop or in the field, to have confidence that they can conduct the observation and provide effective feedback on both safe practices and areas of concern. Several of the companies reporting problems attributed to lack of training had simply told their employees how to do observations, perhaps with a video, during a safety meeting. As one of my mentors used to say, “Preaching ain’t teaching.” Effective training provides the opportunity for practice and feedback to ensure skill development.

Communication of Observation Data, Action Plans, and Successes

The session participants also thought that participants did not know what was done with the information submitted on the observation checklist. Observers turned in their observations and, too often, that was the end of it—they never heard anything back about the picture presented by the observation data and how that information was being used. The most common communication mechanism used by the participants was publication of the Safety Committee (or BBS Steering Committee) minutes. Until they reflected on this practice, I think they really thought of that as communicating. Again, I wish I had polled the audience and asked them to estimate the number or percentage of employees that ever reviewed those minutes!

Communication in BBS initiatives is critical to success. The mechanism for this communication varies, but typically involves sharing/reviewing the information in safety meetings and posting on safety bulletin boards. The most effective mechanism for communication of this information is to review and discuss it in small groups of less than 12 to 15 employees.

Whatever the mechanism, safety committees generally need to communicate three types of information back to employees and those doing the observations. They should provide a summary of the observation data and the picture it provides of safety practices within the organization, in particular practices that are worthy of recognition and areas of concern that are targeted for improvement. In addition, they should communicate action plans resulting from the data and success stories/improvements resulting from past action items.

Production Pressure

The group had an interesting discussion regarding production pressure as a barrier to employees conducting safety observations. We ultimately classified it into two types: real and perceived. Real production pressure is a system issue that ideally is dealt with in the design of the observation process. On an assembly line, for a simple example, an employee may want to conduct an observation but cannot leave his position unless provisions have been made to provide coverage of that position while the employee steps away to participate. The group also recognized that they would experience times when employees could not take the time to do observations, while they also realized that those might be the times when safety observations would be most critical.

Perceived production pressure was very different however, and more related to the expectations of supervision and leadership. This issue overlaps with the next issue of leadership support. The consensus was clear that perceived production pressure was a symptom of supervision or leadership paying too much attention to production issues to the exclusion of safety.

Safety Leadership

The discussion of barriers throughout the morning kept coming back to a single issue, specifically, to leadership’s support of BBS and, more broadly, to leadership’s commitment to safety. Time did not permit us to get into a discussion of leadership commitment, but we did get very specific in discussing the most critical leadership activities that would demonstrate support for BBS observations. On a regular basis, such practices help ensure that employees understand that leadership considers the BBS observations to be an important component of the organization’s safety process.

In many ways, leadership practices are a common thread through all of the issues with BBS observations. Rather than abbreviate the discussion here, or make this article too long for our newsletter, I am going to leave that discussion for the next installment in this series.