Safety is about leadership: that’s not a new concept. Yet, for many years, leadership as it relates tosafety has often been defined as support, which at times translates to just don’t impede the process.

Traditionally, leaders at the highest levels of an organization have fulfilled their mandate for such support by including safety in the corporate mission statement and the operational budget. Of course, behavior-based safety (BBS) professionals have known for quite a while that the success of our efforts hinges upon how adept we are in building leadership support for BBS systems. However, over the years, our interest in, focus on, and definition of leadership support has evolved . . . and for good reason.

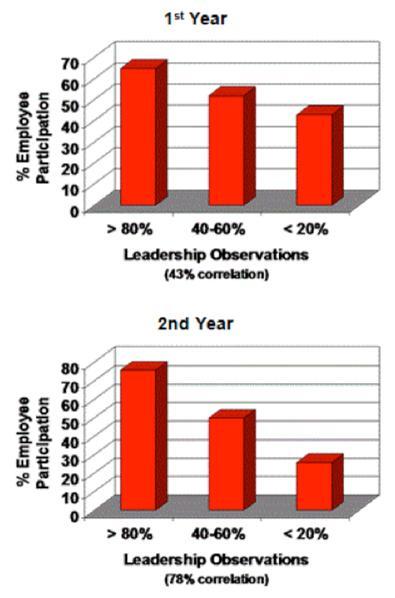

From real-life experience and on-site research we have discovered that leadership safety support—from supervisors to CEO—must be actively visible to be optimally effective. As our company, Quality Safety Edge (QSE), has grown and acquired both large national and international clients, we have changed our requirements of leadership. Why? Because the evidence reveals that doing so is absolutely necessary. For example, the data from one of our early studies, published in Professional Safety magazine, shows that when leaders perform the safety observations/walk arounds in their facilities and are actively engaged in those observations, they attain higher levels of participation in safety observations from employees, a key part of a successful BBS process. (McSween, 2000, see graphs below.)

Leadership is Important — Employee Participation as a Function of Leadership Observations

In facilities where leaders do 80 percent of the observations they are scheduled to do, those facilities average better than 60 percent voluntary employee participation in conducting BBS observations. Our research also reveals that this type of active leadership involvement isn’t only important during the first year of our implementation; it becomes even more important for sustaining such initiatives (see the second graph below). We have replicated this correlation in a variety of other organizations. From my perspective, this correlation is not so much about leadership modeling the behavior, but rather it appears to affect a leader’s credibility. In other words, when the leaders asked their reports to participate by conducting safety observations and feedback, the credibility of that request is higher if the employees see that the leaders make time to conduct safety observations and feedback.

The BBS Umbrella

This discovery was a big deal in the early stages of behavior-based safety because in those early days many of our competitors were implementing behavioral observation systems that only involved employees. (Some BBS consultants still take that approach.) However, with data supporting our approach, we began to routinely track leadership participation. Today, if a company wants a behavior-based safety process but they don’t want us to work with leadership, the bare minimum we will do is track leadership participation in conducting observations. A basic report allows us to see who is doing observations and the number of total observations they’ve done over any period of time, ranging from one month to twelve months. With this report, we can also look at designated observers and/or supervisors, and possibly incorporate that information into the performance appraisal. Typically, this remains the minimum of our intervention in working with leadership when implementing a BBS process, and we still do some implementations that take that approach. More typically however, we now bundle an intervention focused on leaders throughout the organization, and on getting them more engaged in promoting safety, parallel to the implementation of our behavioral safety efforts. In other words, our projects have a dual, separate-but-equal focus on BBS and safety leadership.

In his article “Exploratory Analyses of the Effects of Managerial Support and Feedback Consequences on Behavioral Safety Maintenance” published in the Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, Dominic Cooper makes the overall point that employees need to see leaders doing something to support safety every week. In the case of BBS, it is probably not as critical that the something is a safety observation, but employees need to see leaders at every level engaged in activities that promote safety; whether they ensure that a safety related work order gets addressed, do a safety observation and provide feedback, host a safety meeting, or participate in a safety committee meeting. The takeaway from Cooper’s work is that we really need to focus on visible safety leadership.

Checklists & Agendas

I was very pleased when Atul Gawande’s excellent book, The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Done Right was published, even though I admit I was a bit disappointed that he didn’t mention behavior-based safety. In the BBS field, we have used checklists extensively for some time, including those around leadership behaviors (sometimes as simple as a yes/no pertaining to doing a certain behavior, or a frequency count). One of the things I liked about Gawande’s book is the explanation of the many different ways to structure checklists. As I read this book, I began thinking about our approach to safety leadership and it occurred to me that there are other forms of checklists. I have found it easier, when talking with leaders, to talk about structuring their agenda for safety and what they’re going to cover in their staff meetings, rather than talk about the leadership checklists we have been using for the past fifteen years.

Now I’m talking their language! Senior managers find it more acceptable to talk about creating a systematic review of a structured, recurring agenda at each level of the organization, rather than creating and reviewing data from leadership checklists. The way we talk about it has changed, the format of the checklists has changed, but the process creates the same, or better, level of accountability for leadership practices in support of safety.

Granted, at times a leadership checklist may be more appropriate, for example when there are a variety of kinds of behaviors, the checklist may provide a better prompt or provide better guidance, but I have had better success with structuring the agendas at different levels of the organization. Additionally, agendas have some advantages over checklists. With leadership checklists we are tracking leadership behavior the same way we are tracking the safety practices of employees—entering the data into computers, creating reports, and so forth. When we use a structured agenda, we can basically set that up as a paper-and-pencil effort. Give leaders a notebook with dividers for each meeting or direct report, agenda forms for each section, and they can more conveniently track their safety activities. This approach also provides other advantages, flexibility being one of them. Leaders may be talking about lock out/tag out issues this month, but (possibly driven by the observation data or near-miss data or, worse case, incident data) they can easily change the focus for the following month. They can cascade this method in a systematic way down through the organization, increasing alignment and accountability for both safety and BBS. The table below summarizes the key considerations in each approach.

|

Safety Leadership Checklists

|

Recurring Agenda Items

|

Cascaded Coaching

One of our clients experienced an interesting problem: all of their incidents in one division occurred when a supervisor wasn’t present. This may sound odd, but this particular division was comprised largely of remote workers, usually out in the field and separated by many miles. During the assessment, we looked at the points of contact between each level of leadership and the next, from the Director down through the front- line employees. The Director had a weekly staff meeting with his managers. During this meeting, the first agenda item was always safety. They routinely went beyond the reviewing of incidents and discussed safety observations, near misses, and safety action items. Managers routinely talked with leads via cell phone or in person to discuss daily schedules and assignments. These discussions also routinely included the above- mentioned topics, often adding encouragement to their leads to conduct safety observations. The leads always started each day with a tailgate safety meeting that would include a review of JSA’s, discussing the potential hazards and talking about how to mitigate those hazards. Leads often had multiple jobs, so once the tailgate was complete, they would designate an employee to take the lead on the job and then they would take a portion of the crew and go to another job site. Finally, late in the day, the lead would place a cell phone call to the designated employee to check progress on the job.

They were doing many things right, but we worked with them to fine-tune each point of contact to address practices that would help prevent injuries when the supervisors were not present. We positioned this as leadership development and asked each level to review the quality of the safety efforts at each level, with an objective of improving the quality of observations and discussions about safety on the job. The Director began to ask managers about the discussions they had with their leads around safety and the quality of the tailgates. The managers began to talk with the leads about the quality of the conversations that took place at the tailgate meetings. Did they think that people were involved? How did the employees respond to the discussion? What did you the leads see them doing differently? How did what the designated employee telling you about their observations compare with what the lead observed when doing similar observations? Part of the purpose of the conversations between the lead and the designated employee was to explicitly help the designated employee develop safety leadership skills, and to more explicitly enlist and define the designated employee’s help in preventing injuries.

Finally, and this was perhaps most significant, we added a safety component to the final cell phone call from the lead to the designated employee at the end of the day. We had the leads routinely start these phone calls with a discussion about the designated employee’s efforts to prevent injury. The leads asked if the steps discussed in the tailgate were successful in mitigating the hazards they had identified in their discussion. Further, they asked if conditions changed from what they had planned, and if so, what kind of hazards the change created, what kind of discussion they had with coworkers about the new hazards, what worked for them, and what they might do differently the next time they had a similar job. As with the other levels, we provided a formal agenda to prompt these discussions, though the leads were allowed to adapt the questions to the context of the job. (Sample agenda forms are provided at the end of this article.)

Close Calls (or Near Miss Reporting)

Another thing we’ve done is to add close calls (or more traditionally, near misses) to the BBS observation process. During the feedback discussions, observers simply ask their coworkers if they’ve seen any near misses. This seems to be a much better way of capturing near misses. Observers write the details in the comments section of the observation form. The details are then entered into the computer, and at the end of the month, a list of all comments is generated so that the safety committee has the opportunity to review each one of them and to do further analysis and take action when necessary. This is fairly easy to do and provides a much higher rate of data on near misses, close calls, and minor first-aid kinds of injuries than our clients ever got from any kind of paper recording system, even when compared to providing incentives for reporting these kinds of events. Reporting close calls in conversation is easier for the employees than filling out a formal report of the near incident.

The Safety Leadership (R)evolution

I tell companies if you only put safety first on the agenda, that makes you about a “C” student. Almost all companies that we work with do this even before we start working with them. However, the way most companies do it is by asking, “Did we have any injuries? Was there an incident or near miss?” and then if the answer is no, they go on to talk about other things, such as quality, production, and costs. I have often said that behavioral safety is as much about safety leadership behaviors as it is about employee behaviors. We want every level of leadership asking their reports “What have you done to promote safety in the last week and what are you going to do in the coming week?”

Company leaders at every level need to be visible and having conversations about safety with the employees in their workplace, and they need to talk about the behaviors that promote safety in their meetings at every level. In staff meetings, we want the Director or Site Manager to ask each of his/her direct reports what they did last week and what they are going to do this week to improve or promote safety. That’s much more important than communicating expectations and talking about mission statements. Preaching and taking about expectations is not as critical as first asking about safety and reviewing what is being done to promote safety, and only then providing direction or feedback —thus signaling the importance of safety. These kinds of activities need to occur every week. Therefore, we are very explicit about the purpose of BBS and leadership’s role in creating a culture where we take care of one another.

References

Cook, S., and McSween, T.E. (2000) “The Role of Supervisors in Behavioral Safety Observations.” Professional Safety, October, 33-36